Pilates for chronic conditions: a commentary on current research.

Dr PJ Latey 2024

Abstract

Chronic conditions affect a significant proportion of the population. Pilates is being increasing used to improve wellbeing for many chronic diseases and conditions. Over the last twenty years the increasing popularity and anecdotal promotion of Pilates as an effective way to manage various conditions and musculoskeletal problems encouraged the adoption of Pilates by mainstream medicine. Since that time research on the efficacy of Pilates for a range of conditions has been undertaken by Physical Therapists and independent therapeutic Pilates teachers who were comprehensively trained in the method.

Recent research has found some of the most prevalent chronic diseases and conditions can be managed successfully with therapeutic Pilates. Evidence from systematic reviews report that Pilates is one of the best interventions for managing chronic pain and improving functional performance in those with chronic low back pain, and most effective for improving functional performance and balance for various neurological conditions, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinsonism, and post Stroke.

Although there is very limited quality research on the effect of Pilates on some chronic diseases such as Arthropathies, Asthma and Diabetes, the positive findings suggest Pilates could be a safe management option and offer patients an alternative exercise modality. Similarly, the positive but extremely limited research on the effect of Pilates for other chronic conditions such as Osteoporosis, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and kidney disease suggests further research is warranted.

The positive results of research on the efficacy of Pilates have concurrently encouraged some Pilates training businesses to develop short repertoire courses for teacher training. However here is no independent oversite of competencies to provide Pilates as a treatment modality. Therapeutic Pilates is not just a list of exercises, but Pilates as a mind-body movement modality no longer has higher educational pathways or consistent standards of practice. Further the uptake of this modality by those with minimal training requirements may lead to its loss of efficacy and possibly harm.

This commentary presents a summary of the most up to date evidence examining the effect on chronic conditions and problems, of Pilates provided by comprehensively trained independent Pilates teachers and registered allied health professionals. Current evidence shows that as a mind-body movement modality Pilates is a safe and effective intervention for managing the consequences of many chronic conditions.

Key words: Pilates, therapeutic exercise, mind-body movement, chronic disease management, rehabilitation

1.1 Background

Pilates exercises applied therapeutically have been shown to reduce pain and disability, and improve posture and enhance quality of life, by improving core stability, strength, flexibility, posture, muscle control, proprioception and body awareness [1]. There is no research published on the efficacy of GymPilates including fitness Mat Pilates, reformer Pilates, barre Pilates etc. Similar to other general exercise modalities [2], large group GymPilates classes may be beneficial when taught to a fit and well client as is general exercise/physical activity [3].

None of the positive findings on Pilates research for specific conditions or pathologies cited in this commentary is likely to be relevant, have efficacy or be safe when provided in a gym setting and or by group Pilates fitness instructors or personal trainers. Registered allied health providers who have not completed a comprehensive or therapeutic Pilates certification recognised by a professional Pilates association are also unlikely to be able to safely and effectively provide Pilates services associated with the positive research published on Pilates discussed below.

For brevity while discussing the effect of comprehensive, therapeutic or clinical Pilates this paper will primarily use the term Pilates when referring to research on comprehensive tailored sessions or population specific small group Pilates in Section 2.

1.2 Chronic disease

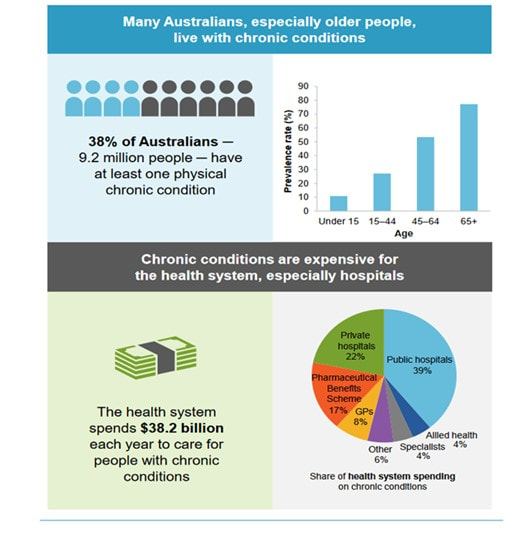

Chronic conditions affect a significant proportion of the population, with the prevalence of various conditions experienced by Australians noted in Figure 1. Previously mainstream medical funding, research and education has focussed on interventions such as surgery, pharmacology, and short-term physical rehabilitation. As more people are surviving the acute phase of their illnesses and people are living longer effective management of chronic conditions has become vital. Due to both the cost of managing chronic problems on a personal level and the substantial public funding required.

Government supported chronic disease management programs were introduced into health services in Australia in 2007. While insurers are able to provide benefits for a range of treatments under chronic disease management programs there are no regulated minimum benefits. Eligibility of benefits for risk equalisation arrangements is also restricted to planning and coordination services and treatments provided by registered allied health providers, limiting options for management of those with chronic conditions. Natural and complementary therapies, such as Pilates provided by self or unregulated providers were not included in the risk equalisation arrangements. In addition, after an Australian Federal government review in 2015 on selected Natural Therapies 16 were excluded from private health insurance such that private health insurance funds were not able to provide benefits for Pilates services. However, interestingly physiotherapists lobbied government such that physiotherapists (and other allied health workers) could provide Pilates-based treatments that were able to be rebated by PHIFs as long as it was within their scope of practice and that treatment did not entirely consist of Pilates (circular PHI 69/18)[4]. These two criteria have yet to be elucidated.

Management of chronic diseases and chronic pain has been commonly with various forms of pain relief medications, surgery and physical therapy. Research on various forms of physical therapy, including the use of interferential current [5], taping [6], manual releases and motor control exercise programs[7, 8] have reported conflicting or poor results. Increasingly from the early 2000’s people with chronic diseases and problems began to self-manage using Pilates, tailored to their specific needs. At the same time some physiotherapists began additional comprehensive training as Pilates instructors. This training was primarily provided by experienced independent Pilates teachers. Research on the efficacy of Pilates for various chronic problems began to be undertaken by both Physiotherapists and independent Pilates teachers.

There is now a significant body of research on the efficacy of Pilates. Numerous systematic reviews report the positive effects of Pilates for example, for improved general health and functional body composition [9], on a range of pathologies and conditions such as chronic low back pain, general wellbeing [10, 11]and age related decline [12].

This paper will provide a commentary on recent systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on Pilates for managing chronic problems and conditions. Research findings on the effect of the complementary mind-body movement modality of Pilates on chronic conditions and diseases are reported by condition as per Figure 1. Effective support for those with chronic problems is a growing area of concern for public health as one in two Australians are reported as living with a chronic problem https://www.vu.edu.au/mitchell-institute/australian-health-tracker-series/australia-s-health-tracker-2019 .

The most prevalent chronic conditions experienced in Australia in 2022 were:

- Mental and behavioural conditions – 26.1%

- Back problems – 15.7%

- Arthritis – 14.5%

- Asthma – 10.8%

- Diabetes – 5.3%

- Heart, stroke and vascular disease – 5.2%

- Osteoporosis – 3.4%

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) – 2.5%

- Cancer – 1.8%

- Kidney disease – 1.0%.

Figure 1.

2.1 Mental Health and Mood

As a mind–body intervention therapeutic Pilates fundamentally includes recognition of the importance of emotional and behaviour factors which can directly affect our health[13]. Mindfulness, self-compassion and life satisfaction are linked and enhanced with the practice of Pilates [14]. Although there is limited evidence, a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of Pilates on mental health outcomes concluded that Pilates improves mental health outcomes including symptoms of depression and anxiety, feelings of energy and fatigue [15]. Their findings suggest that Pilates may improve psychological outcomes among individuals regardless of health status, which is consistent with positive results reported in another systematic review investigating effects of physical fitness and well-being in the elderly [16]. These results are similar to the positive small to moderate but positive findings reported in a systematic review on the effects of mind-body interventions including Pilates on quality of life in older adults (g = 0.14, 90% CI [−0.01, 0.29]; p = 0.12), [17].

In addition, a systematic review on the physiological and psychological benefits of Pilates in healthy older adults and older adults with a clinical condition report moderate to large effects (SMD: 0.62; 0.83) for improved psychological health parameters [10] . When Pilates interventions were compared to an inactive control quality of life, depression, sleep quality, fear of falling, pain, and health perception significantly improved (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) regardless of their health status [10].

Two systematic reviews on the effect of Pilates on conditions associated with women’s health report a positive effect of Pilates on several mental health outcomes[18, 19]. A Systematic Review on women with breast cancer found Pilates had a positive and significant effect on several emotional (quality of life, mood, pain) parameters [18]. Prenatal anxiety has also been reported to be reduced with the practice of Pilates and may prevent anxiety symptoms [19].

Kinesiophobia is the avoidance and fear of movement and can be a more dominant factor in determining the level of physical activity than pain in an older population [20]. A study on the effect of Pilates exercises on Kinesiophobia and other symptoms related to osteoporosis found Pilates training positively effects Kinesiophobia and quality of life [21]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of the Pilates method on Kinesiophobia found favourable outcomes with Pilates compared to minimal intervention or no treatment in reducing Kinesiophobia associated with chronic non-specific low back pain, with a moderate quality of evidence [22].

2.2.1 Back problems - Spinal pain

There is a large body of research on the positive effect of Pilates on chronic musculoskeletal pain, particularly spinal pain. The integration of mind and body balanced with breath control using modified Pilates may improve quality of life for some conditions[23, 24] and may be more effective than other physical therapies on upper extremity pain and function [18]. A systematic review on chronic musculoskeletal conditions reports a significant reduction in back pain, neck pain, and pain associated with knee osteoarthritis and osteoporosis with Pilates as well as a significant increase in adherence to exercise [25].

2.2.2 Neck pain

A systematic review on Pilates for neck pain has reported Pilates reduces neck-related pain and improves function [26] . Another systematic review on the effect of Pilates compared to other interventions for neck pain reports, based on low certainty of evidence, Pilates was no better than other treatments in the short term. However, there was moderate certainty evidence that Pilates could be better than usual care for reducing pain and disability in the intermediate term [27]. In contrast, a more recent systematic review summarising the different exercise modalities used for managing chronic neck pain reports low to high certainty of evidence for various exercise types with no optimal exercise type for managing chronic neck pain [28].

2.2.3 Chronic low back pain

Chronic low back pain effects a significant percentage of the population at any one time and is a common cause of disability [29]. There is a substantial body of research on various forms of exercise for managing low back pain. Over the last decade numerous systematic reviews have examined evidence on the effect of Pilates for low back pain. One review found Pilates exercise provided improvements in pain and functional ability compared to usual care and physical activity in the short term, but no difference when compared to other forms of exercise at 24 weeks of exercise [30]. This review reported that the majority of included studies had a high risk of bias [30]. For those with low back pain Pilates is intended to improve deep muscle stability and control of the spine whilst reducing the activity of superficial muscles, as well as to improve posture and body awareness, so as to reduce pain and disability [31]. A Cochrane review reported low to moderate quality evidence that Pilates is more effective than minimal intervention, but their results also showed no conclusive evidence that Pilates was superior to other forms of exercise [32].

However, two more recent Systematic reviews and network meta-analysis report Pilates as the most effective treatment modality in reducing chronic low back pain when compared with all other types of physical exercise[29, 33]. The Cochrane review by Hayden and colleagues, report exercise therapy had the largest reduction of pain intensity in those with low back pain with a clinically important difference and a moderate certainty of evidence for improving functional limitations [11].A further network meta-analysis results show Pilates was more effective than all other types of exercise, compatible with a clinically important difference in reducing pain intensity, (most likely MD range -9.3 to -17.5)[11]. The network analysis comparing various exercise types with each other on functional limitation improvements show moderate differences compatible with clinically important differences in functional limitation outcomes (in order of efficacy) for Pilates, McKenzie therapy and flexibility exercises compared with other conservative treatments (most likely MD range -5.3 to -12.4) [11]. Similarly, another systematic review found practicing Pilates has the highest likelihood for reducing pain and disability for those with chronic low back pain. This systematic review with network meta-analysis report on SUCRA analysis, Pilates had the highest likelihood for reducing pain (93%) and disability (98%) [34].There is also moderate-quality evidence that Pilates exercise may reduce pregnancy related low-back pain more than usual prenatal care or no exercise [35].

Interestingly, a systematic review of systematic reviews on the effects of different types of exercise on chronic low back pain found low-to-moderate evidence that Pilates is no better than other exercises but better than minimal interventions; with only small effect sizes found [36]. The authors also state “Pilates and MCE (motor control exercises) might be considered comparable as exercise type but differ in that MCE seems to be more often supervised, individualized, and performed as a graded program, starting with low load and specific exercises.” [36]. This statement is not supported by evidence and conflicts with a review on MCE by Ganesh and colleagues[8], who noted that most MCE studies considered in their review ‘’did not adhere to the principles of these exercises’ and that ‘’There is wide heterogeneity in the understanding, administration, and progression of exercises. The exercises were implemented without considering the potential for neuroplasticity and the principles of motor learning.”[8].

Subsequent to the Cochrane review on exercise therapy for chronic low back pain [29] a further review was carried out to inform the WHO guidelines on managing chronic low back pain [37]. Verville and colleagues (2023) review reports low or very low certainty evidence, that ‘’pain reduction was associated with aerobic exercise, Pilates and motor control exercise; improved function was associated with mixed exercise and Pilates’’ [37].This review examined very limited evidence (search dates 28th April 2018 to 17th May 2022). RCTs previously published were only included in their supplementary synthesis. The 13 studies included were allocated into nine exercise types. Thus, this review findings are based on one to three RCTs for each different exercise type. Interestingly, Cancelliere and colleagues(2023), in an associated paper on chronic low back pain noted that much research on exercise therapy for managing chronic low back pain has both methodological and reporting issues[38]. Further, that chronic low back pain is a “complex phenomena that cannot be reduced to simplistic explanations or approached with a one-size-fits-all intervention”[39]. Even so, while there are slight variations in the findings of the systematic reviews, Pilates is consistently reported to reduce pain and improve function in those with chronic low back pain.

2.3 Arthropathies

Arthritis may be degenerative joint specific or an inflammatory systemic disease[40]. Arthritis can cause joint deformity, dysfunction, and muscle wastage [41]. As Pilates improves muscle activation, strength and flexibility [9] it would be an applicable intervention for the various forms of arthritis. Although there is very limited quality research on the effect of Pilates on the various forms of arthritis current evidence demonstrates that Pilates is effective for managing arthritic pain [42-44].

2.3.1 Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

A review on juvenile idiopathic arthritis found the addition of Pilates exercises may be more effective for decreasing pain intensity, improving cardiorespiratory fitness, augmenting functional ability, and promoting quality of life in children with Juvenile idiopathic arthritis than conventional Physiotherapy alone (p = 0.001 to p< 0.05) [42].

2.3.2 Osteoarthritis - Knee

it is well established that physical activity and exercise therapy reduce symptoms and improves physical function of individuals with knee osteoarthritis (OA) [45]. There is very limited research on managing knee conditions with Pilates. Even so a systematic review on osteoarthritis of the knee reports Pilates is effective for reducing pain and gaining strength [43]. Another systematic review on chronic musculoskeletal conditions also reports Pilates was effective for managing knee OA and assisted in the reduction of pain but was not more effective than other exercise [25].

2.3.3 Arthritis - rheumatic diseases

There are a number of inflammatory rheumatic diseases[46]. Rheumatoid arthritis is a painful, debilitating disorder that greatly affects physical function [47]. Sedentary behaviour in Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) s linked to heightened inflammation, and is highly pervasive in RA, likely because of compromised physical function and persistent fatigue. Since high sedentary behaviour may exacerbate the inflammatory process in RA [48], providing a safe mind-body movement modality such as Pilates may provide an accessible option for those with RA.

A systematic review on the effect of complementary therapies on ankylosing spondylitis(AS), rheumatoid arthritis(RA), and fibromyalgia syndrome FMS) reports Pilates can be considered a safe, and potentially effective exercise approach in AS, RA, and FMS management. However, the authors note the number of high-quality articles is very limited, particularly for RA [44].

2.4 Asthma

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease, substantially affecting the quality of life of people of all ages [49]. While improved respiratory function and breath training is fundamental to the practice of Pilates [13, 50, 51] there is very little research reported on Pilates for asthma and no systematic reviews found. Even so, a limited number of studies report on the positive effect of Pilates on respiratory function in different sedentary populations [52, 53].

There is evidence of the effect of other mind-body modalities such as Yoga having a positive effect on Asthma[54]. A systematic review on complementary health modalities report breathing exercises may have some positive effects on quality of life, hyperventilation symptoms, and lung function[55]. However, Pilates was not included as a search word for this otherwise comprehensive review. The relationship between asthma and physical activity is multifaceted, and Pilates may potentially have a reversing effect to the negative loop of exercise exacerbating some symptoms, by enhancing physical activity and breath control [56]. This hypothesis is supported by the results of a systematic review on Pilates and cardiorespiratory function that found very low to low certainty of evidence that Pilates has a large positive effect on respiratory function if the duration of the intervention was between 2-3 months and at least twice a week [57].

2.5 T2 Diabetes

Diabetes is a disease effecting about 10.5% of the adult population globally[58]. Various forms of exercise can assist in maintaining health for those with all forms of diabetes [59]. There is very limited evidence on Pilates for T2Diabetes and what is available presents a confusing assessment of current research. A systematic review on exercise as a complementary medicine intervention in T2 Diabetes only searched for physical activity/exercise and various types of fitness activities, with no complementary mind-body movement modalities included in search terms [60]. In contrast, another systematic review on the effect of Pilates on glucose and lipids found Pilates interventions could significantly improve blood glucose and lipids metabolism for diabetic patients [61]. These two different review search strategies and subsequent results highlight the need to distinguish between physical exercise as opposed to the complementary modality that is therapeutic Pilates.

However two recent RCT’s found Pilates can improve glycemic control in T2Diabetes [62], and improve core strengthening balance, gait, proprioception and HbA1c[63]. Exercise confers remarkable benefits to those with diabetes [64]; even so, the challenges to encouraging patients with diabetes to exercise are formidable [65]. High BMI and body fat are associated with Diabetes [66]. The positive findings of a recent systematic review that reports Pilates may significantly reduce body weight (MD = −2.40, 95% CI: [−4.04, −0.77], P = 0.004, I2 = 51%), BMI (MD = −1.17, 95% CI: [−1.85, −0.50], P = 0.0006, I2 = 61%), and body fat percentage (MD = −4.22, 95% CI: [−6.44, −2.01], P = 0.0002, I2 = 88%) in overweight or obese adults [67]. Another reviews reports Pilates induces positive psychophysiological adaptions [68] in overweight and obese individuals suggest practicing Pilates may be beneficial for this patient group. Although the quality of the evidence was low these results support the inclusion of Pilates for the conservative management of diabetes and obesity.

Up to about 50% of adult diabetics can be affected by peripheral neuropathy (PN) [69], which is linked to foot ulceration[70]. Sedentary behaviour is one of the strongest variables contributing to the development of diabetic foot ulcers [71]. However, encouraging those with diabetes to exercise is difficult, particularly if they have peripheral neuropathy. Even so, exercise can be beneficial to those with PN [72]. Since therapeutic Pilates pays attention to safe mindful footwork[73], Pilates may be an effective and safe activity to minimise sedentary behaviour in those with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy.

2.6 Stroke and Neurological conditions

People with neurological related conditions including Stroke, Multiple Sclerosis, and Parkinsonism can experience high levels of compromised balance and limited functional movement ability[74-76].There is a significant amount of evidence that Pilates is more effective than other physical interventions for these neurological conditions.

A systematic review on complementary and integrative health interventions for post-Stroke rehabilitation reported improvements in functional balance, standing and dynamic balance, reaction time, maximum excursion, and quality of life of participants in the Pilates studies [77]. Similarly, another systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of Pilates in a post-Stroke population found moderate quality of evidence for Pilates exercise significantly improving balance compared with conventional Stroke physiotherapy and some limited evidence for improvements in quality of life and gait parameters in post stroke individuals, when compared to conventional physiotherapy [74].

In those with Multiple Sclerosis, research found that Pilates significantly improves balance and functional ability. A systematic review on Pilates for Multiple Sclerosis notes the research was of poor to good quality. The included studies results show practicing Pilates induced a range of physical benefits, but Pilates was not significantly better than other physical interventions [78]. Similarly, another recent systematic review reported Pilates can improve balance and balance confidence for those with Multiple Sclerosis however it is unclear if it is more effective than physiotherapy interventions [79]. As well as improved balance Pilates has also been reported to improve gait, physical-functional (muscular strength, core stability, aerobic capacity), body composition, and cognitive functions in those with Multiple Sclerosis [80]. This systematic review reports on 17 studies of those, ten were of good quality (PEDro), and seven had low risk of bias (RoB-2). In addition, this review noted there was very good adherence to the Pilates intervention (average adherence >= 80%) [80].

In those with Parkinson’s disease, research shows that Pilates significantly improves functional mobility and balance [81]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on physical exercise for people with Parkinson’s disease concludes that most types of physical exercise are beneficial for people with PD [82]. However Pilates studies were excluded from this Cochrane review possibly due to the taxonomy to determine mind body exercise which was adopted from the taxonomy of a systematic review on falls interventions [83]. Interestingly a commentary on rehabilitative therapies in Parkinson’s disease groups Pilates therapy as a subset of Physical therapy and reports a number of positive findings for Pilates for Parkinsonism [84].

In addition, a systematic review on mind body interventions which includes Pilates, reports Pilates was significantly more effective than any other physical exercise program for improving functional mobility and balance in people with Parkinson’s disease [81]. This systematic review of mind-body exercise (MBE) with a network meta‑analysis examined and compared Yoga, Tai chi, Pilates, Qigong, dance and physical exercise rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease. All MBE were significantly more effective for improving functional mobility than physical exercise rehabilitation, with Pilates being the most effective in improving functional mobility (MD: − 3.81; 95% CI (− 1.55, − 6.07) and balance performance (SMD: 2.83; 95% CI (1.87, 3.78) [81]. Another systematic review with network meta-analysis comparing 24 exercise modalities on postural instability in adults with Parkinsonism [85] found Pilates was the most effective exercise intervention for improving proactive balance. Further this review found Pilates was one of only four exercise modalities that significantly improved over all balance ability [85].

2.7 Bone Density - Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis or low bone density can significantly increase the risk of fracture and cause pain [86]. A review of studies of Pilates in men and postmenopausal women aged ≥50 years with low bone mineral density (BMD), history of fragility fracture, or moderate-high risk of fragility fracture found Pilates may improve physical functioning and quality of life in women with Osteoporosis. However, evidence of the effect of Pilates on BMD, falls, fractures, or adverse events is very limited [87].

A systematic review on the effect of Pilates on people with Osteoporosis found practicing Pilates was associated with pain relief, improved functionality and quality of life [88]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of Pilates and Yoga to improve bone density in adult women, notes that despite the non-statistically significant results, the BMD maintenance in the post-menopausal population, when BMD deterioration is expected, could be understood as a positive result added to the beneficial impact of Pilates-Yoga in multiple fracture risk factors, including but not limited to, strength and balance [89].

While studies on Pilates for Osteoporosis show no significant positive increase in BMD, practicing Pilates has been shown to reduce pain [25] and improve functionality for those with Osteoporosis [88]. This is likely due to the way Pilates movements are taught. The tailored resistance-assistance exercises are performed primarily in supine, prone and side lie on mats and with Pilates apparatus. The understanding of the effect of gravity and the ability to manipulate the effect of gravity [90] while maintaining bone health is likely to increase the safety of the intervention and minimise fracture risk and is a fundamental positive difference from general exercise.

2.8 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD is “characterized by the presence of airflow limitation due to chronic bronchitis or emphysema” [91]. Improving mobility is an important factor in self-managing COPD [92] as well psychosocial needs require prioritisation [93]. While evidence is very limited a systematic review with a network-meta-analysis found Pilates one of the best exercise interventions for COPD with exercise capacity measured by the 6 minute walk the second highest SUCRA score after urban exercise walking. Their data also showed that these interventions obtained the best benefits when supervised [94]. Diaphragmatic breathing are physical therapy interventions that effectively promote pulmonary function and exercise capacity in patients with COPD[95]. The very limited evidence that supervised Pilates has a positive effect on COPD [94], suggests further research is needed as breath training coordinated with whole body movements are integral to Pilates[50, 96].

2.9 Cancer

Many people with cancer can benefit from practicing Pilates, particularly post Cancer treatments. Most research has been undertaken on Pilates post breast Cancer[97]. Pilates has been reported to have a positive effect on some consequences of Cancer and improve exercise tolerance for those with breast Cancer [98]. Another systematic review on Pilates for recovery in women with breast Cancer observed that even though there was limited research, Pilates produced significant improvements in range of motion, strength, flexibility, quality of life and pain reduction [97].

A systematic review on the efficacy of pelvic floor muscle exercise (PFME) for post-prostatectomy incontinence concluded that PFME had a positive effect on incontinence post-prostatectomy [99]. This review notes that Pilates exercise programs show a large significant positive effect on quality of life and improved urinary continence for incontinence postprostatectomy with a moderate certainty of evidence. Also, studies have shown Pilates exercise as effective as conventional pelvic floor muscle exercise to speed up continence recovery in those with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, with a higher rate of fully continent patients when compared to a control group [100, 101].

2.10.1 Kidney Disease

There is a minimal amount of research on Pilates for kidney disease. Kidney disease is associated with incontinence [102] and there are some positive findings on urinary incontinence for different populations[99]. Even so, a systematic review on the role of mind-body interventions in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients reports that Pilates may provide significant improvements in quality of life in this patient cohort, however the evidence is very limited[103]. In addition, since exercise is reported to be more effective than sedentary behaviour or other active control for improving depression and anxiety symptoms in those with chronic kidney disease[104], further research in Pilates for managing this chronic disease is warranted.

3.1 Discussion

Chronic conditions and diseases effect a substantial proportion of the population (Figure1 & 2). The management of chronic disease by mainstream medicine has up to recently, been similar to acute disease management [105] via increased complex pharmacology, surgery or with time limited manual rehabilitation or physical therapy with a range of interventions and/or set exercise programs that focus on dose and load, limiting optimal care [106]. However, the management of many chronic diseases or complex conditions requires very different strategies and therapeutic approaches from typical medical practice. Many mainstream interventions show limited efficacy and may even cause harm [107].

The complementary mind-body movement approach using therapeutic Pilates has been shown to reduce pain, improve balance, functional movement and quality of life for many chronic conditions and diseases[11, 12, 80, 98]. This is achieved in conversation with the client and observing any body movement dysfunction, breathing and postural habits, then providing tailored exercises with gradual retraining and unpicking dysfunctional compensatory patterns of movement in a mindful way in conjunction with client guidance[108]. Discerning observation and listening to the client underpins high levels of personalised supervision of exercise performance skill to reduce pain and improve functional abilities[109].

Some systematic reviews report that the potential beneficial effects of Pilates are not significantly greater than those derived from the performance of other physical therapies. Such as for women with breast cancer managing the impact of breast-cancer related symptoms [18], for those with multiple sclerosis[110],or for neck pain[27]. These systematic reviews all note the lack of high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of Pilates for a range of problems and conditions, with most reviews reporting research on Pilates compared to an inactive control. However, there is increasing research comparing various physical interventions with the mind-body movement modality that is therapeutic Pilates[25].

For some chronic diseases and conditions Pilates has been found to be the best form of intervention compared to all other physical therapy interventions. This includes but is not limited to, Pilates for reducing pain in those with chronic low back pain [11], for improving function in neurological conditions such as Parkinsonism [81] and balance post-stroke [74] and decreasing fear of falling in older people [111]. These positive findings on the efficacy of Pilates for reducing pain and improving functional performance has led to it being increasingly incorporated into a variety of treatment programs. Unfortunately, the uptake of Pilates by mainstream medicine has not been matched by tertiary education in therapeutic Pilates.

The increasing certainty of evidence on Pilates for the substantial reduction in pain and improved function, in those with chronic lower back pain [11, 34] could be in part due to the increasing amount of research published on chronic low back pain management. Unfortunately, this is not reflected in improved quality research support for Pilates at a tertiary level, such as funding for large scale trials. The reporting of Pilates exercise programs even in moderate-to-high quality RCTs for the management of lower back pain remains incomplete [112]. Further research with clear descriptions of the intervention, any tailoring and progressions are needed to ensure the correct application of Pilates interventions. Numerous reviews on Pilates report the most effective Pilates exercise programs are personalized and contextualized to individual participants[34], improved consistent education of Pilates providers is necessary.

There is a significant amount of evidence that Pilates is more effective than other physical interventions for many neurological related conditions [74, 80, 81, 85]. It is likely that the combination of the mind-body aspect of the Pilates method is particularly effective for managing neurological conditions. The focussed attention, coordinated breath, assistance to lengthen as you strengthen with postural training from the core and specificity of attention to good performance skills directly addresses many of the neuromuscular compromises inherent in these conditions, such as functional mobility and balance [81]. This highlights the importance of providing thorough training in the person-centred mind-body intervention that is therapeutic Pilates to ensure neurological based diseases or conditions are managed wholistically and effectively.

Although there is very limited quality research on the effect of Pilates on some chronic diseases

such as Arthritis [42-44], Asthma [57] and Diabetes[61], the positive findings suggest Pilates could be a safe management option and offer patients an alternative exercise modality. Similarly the positive but extremely limited research on the effect of Pilates for other chronic conditions such as Osteoporosis [88], COPD [94], and Kidney disease [103] suggests further research is necessary. In addition, the consistent positive results of systematic reviews reporting on the use of Pilates for managing breast cancer survivors’ physical and psychological wellbeing post medical cancer treatments [18, 97, 113, 114] suggests that Pilates should be an accessible exercise option.

However, while there are consistent positive findings for improved continence postprostatectomy with Pilates[99], there is minimal and conflicting evidence of the efficacy of Pilates for improving female incontinence. Urinary incontinence among group fitness instructors including female Pilates teachers (GymPilates) has been reported as 26.3% [115]. This suggests GymPilates is contraindicated for those with pelvic floor problems. Indeed, GymPilates may contribute to pelvic floor problems and urinary incontinence, due to the nature of the classes[116]. Urinary incontinence in women is reported to only improve with correct cueing of pelvic floor engagement [117] this is unlikley to occur without quality teaching skills and demonstrates the need for quality education when providing Pilates and the recognition of the potential detrimental effects GymPilates may have on continence.

4.1 Exercise adherence

Physical activity and exercise such as Pilates can improve pain, physical function and quality of life in adults with chronic pain [118]. However as with many conditions exercise adherence remains challenging. For example, factors affecting adherence to exercise in those with Osteoarthritis are reported as socioeconomic status, education level, living arrangements, health status, pacemakers, physical fitness, and depression [119]. Improving adherence could have a significant impact on longevity, quality of life, and health care costs.

Financial incentives increase exercise attendance in the short term, with assured incentives and objective behavioural assessment increasing effectiveness[120]. Currently financial benefit is skewed to the registered allied health provider, who may or may not have sufficient Pilates education to assess appropriately. The design of an exercise program is another key factor in maintaining adherence. Tailored exercises, the use of various exercise types with proven evidence of efficacy for the target population, a frequency higher than once per week, and a moderate duration of the program may be key factors to achieve high levels of adherence [121]. Tailoring Pilates exercises and ensuring correct exercise performance skills are fundamental to being a comprehensively trained Pilates provider[122]. Multiple systematic reviews on Pilates report significantly high exercise adherence levels in those practicing Pilates[25, 80, 123].

5.1 Adverse events

Adverse outcomes or events were rare in the numerous research noted in this commentary. It can be inferred that initial evidence points to the safety of Pilates method exercises as a rehabilitation tool [124] in most patient groups such as for osteoporosis [21], post-stroke rehabilitation[74] and the older adult with or without clinical conditions [10], chronic musculoskeletal conditions[25] and low back pain[11].

However two case reports one on spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm with perforation of the stomach during Pilates [125] and another on simultaneous bilateral should dislocation in group class [126] are salutary reminders that Pilates inappropriately supervised can cause harm.

6.1 Quality of evidence and risk of bias

In general, research on the efficacy of therapeutic Pilates for various chronic conditions range from low to moderate certainty of evidence. The Systematic reviews included in this commentary reported fair to high quality studies with the majority reviews noting an increase in higher-quality studies in the most recent studies. The downgrading of the quality of evidence because of high risk of bias was often due to the inability to blind the participants to the intervention, or the assessor was unable to be blinded. Other reasons for downgrading the quality of the evidence included low numbers of participants with imprecision frequently an issue, meaning the effective sample size was often small with some studies underpowered to detect the between-group differences. Pooling too heterogeneous results could result in inconsistent findings and an inability to draw any meaningful conclusions. Indirectness and publication bias were lesser common reasons for downgrading. However, the generally accepted minimum number of 10 studies needed for quantitatively estimating funnel plot asymmetry was often not available.

6.2. Bias due to exclusion criteria

Many systematic reviews on exercise as therapy for chronic diseases exclude Pilates as an intervention because it is simply not included as a search term in the search strategy. This includes on Asthma [55], and Diabetes [60]. Other Cochrane reviews on various forms of exercise, such as for Parkinsonism [82] and on falls prevention [83] exclude Pilates as it does not meet the exercise taxonomy requirements of the search terms. Yet another Cochrane review on Cochrane systematic reviews on exercise physical activity and health outcomes includes Pilates [3]. Some systematic reviews on complementary modalities only focus on traditional mind-body movement systems such as Yoga and Tai chi and do not include Pilates as a search term [127]. The inconsistency in search inclusion and exclusion criteria is likely to have a significant impact on data reviewed and may skew the results of systematic reviews examining evidence of physical exercise, mind-body movement modalities and any effects that these interventions might have on a given population.

7.1 Limitations

This commentary on recent research on some chronic diseases and conditions has several limitations. Search strategies were limited to systematic reviews on the selected chronic diseases, and Pilates, exercise and mind-body interventions published from 2018 to 2023. Multiple Systematic reviews on some topics led to considerable overlapping of evidence in selected conditions. However, as some reported different outcome measures similar topic systematic reviews were included, and the different outcome measures discussed. RCTs were only referred to in this paper if no Systematic review reported on diseases or conditions relevant to those listed in this paper. Another limitation to this commentary is that a search of multiple data bases was not undertaken at a single designated date, therefore published papers could be missed or inadvertently excluded leading to bias. A further limitation is the commentary reports only the findings of systematic reviews published in English as no research published in another language were accessed potentially further biasing the findings of this commentary.

8.1 Therapeutic Pilates a distinct complementary alternative for chronic disease management

Considering the interest and costs associated with chronic disease management (Figure 2) taken by the various government agencies [128, 129] and the proven efficacy of Pilates for managing many chronic problems, re-evaluating the role of complementary mind-body Pilates is worthy of consideration. Most importantly, physical inactivity, itself, often plays an independent role as a direct cause of speeding the losses of cardiovascular and strength fitness, shortening of health span, decreases quality of life, increases health care costs, and accelerates mortality risk [130]. Mind-body practices may provide an opportunity for physical activity for individuals suffering from chronic health conditions [131].

Figure 2. Chronic conditions are common and costly

https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/chronic-care-innovations/chronic-care-innovations.pdf

https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/chronic-care-innovations/chronic-care-innovations.pdf

Patient self-management can improve outcomes for those with chronic diseases [132]. Providing consumer choice, with equivalent funding and education support for the mind-body practice of Pilates by non-registered allied health professionals would expand the care options for chronic disease management and potentially reduce the need for intensive forms of health care. As self-management support is most effect in those with some chronic diseases [133] removing any financial or structural barriers, to clients who undertake the physical activity of their choice[123], such as Pilates, may improve exercise adherence. This would reduce the considerable costs of hospitalisation(Figure 3) due to poor chronic disease management [134] and the sequelae of increased disability.

Regulating education, competencies and skills rather than professions as well as reducing the number of clinical transactions [135, 136] may support patient self-management of their chronic disease. Recognising that some aspects of health care can be delivered safely and effectively by professionals with different skills and experience has the potential to contribute to health systems efficacy when undertaken in conjunction with adequate planning, resources, education, training and transparency. Matching rewards and indemnity to the levels of skill and risk required to perform a particular task, not professional title will enhance health care effectiveness, ensuring that those taking on new tasks and roles have adequate training and skills is fundamental to safe practice [137].

The evidence that Pilates as a mind-body movement modality is significantly more effective than any other physical therapy interventions for managing many painful and debilitating chronic conditions is mounting[11, 74, 81]. However, the confusion of what is Pilates in the research area reflects one of the problems with Pilates in the general population and in health regulation, who and what providers have relevant qualifications or skills. This directly leads to concerns about the decision (circular PHI 69/18)[4] for giving or denying financial support via government or private health insurance rebates for the provision of Pilates. Currently it appears being any registered health provider is more important than being educated to provide therapeutic Pilates. The bias towards registered providers, has no evidential basis and reduces consumer choice.

Interestingly many systematic reviews point out that Pilates needs to be provided by a fully qualified Pilates teacher and that experience and quality of the supervision is vital for efficacy[11, 25, 138]. The mind-body movement modality that is therapeutic Pilates is not gym exercise and not mainstream physiotherapy it is a person-centred individually tailored therapeutic movement intervention grounded in the principle of a balance of mind and body, in a moving meditative respiratory process being fully in the moment, feeling, thinking and doing [108]. A distinct alternative that complements mainstream medicine. Indeed, research reports the effectiveness of Pilates on reducing pain, disability ,improving physical function, and quality of life in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal conditions is no different when provided by comprehensively trained independent Pilates teachers, or physiotherapists who are comprehensively trained [25]. Therefore, whoever the provider adequate training in Pilates is vital.

9. Conclusion

There is a growing body of research on the positive effect of therapeutic Pilates to reduce pain and improve quality of life for many chronic conditions and problems. Research shows therapeutic Pilates is the most successful intervention for managing chronic low back pain and is significantly better than any other form of intervention for reducing pain, disability and improving functional performance in those with chronic low back pain. Pilates is also better than any other forms of physical activity or interventions in improving functional mobility in Parkinsonism and post Stroke and has a positive effect on the consequences of Multiple Sclerosis.

There is increasing evidence that those with a variety of mental health issues and mood disorders can benefit from practicing Pilates. While there is only limited evidence of the efficacy of Pilates for some chronic conditions such as arthritis, asthma, diabetes, osteoporosis and COPD, Pilates could be a safe alternative for ongoing management. Even though there is very limited evidence for those with cancer, kidney disease and incontinence, Pilates can significantly improve quality of life for these conditions. However, for female incontinence quality informed Pilates supervision is vital for the method to have any efficacy and not exacerbate the condition.

However, Pilates as a mind-body movement modality currently has no higher educational pathways or consistent standards of practice which urgently needs to be rectified. Ensuring service providers are fully educated and financial support is directed to allow consumers to choose their pathway to maintain wellness will improve adherence to practice.

The uptake by fitness and registered allied health providers of this modality with minimal training requirements may lead to its loss of efficacy and possibly harm. Quality education and further high-quality research needs to be undertaken in therapeutic Pilates to improve outcomes for those with chronic diseases.

Clinical relevance

Comprehensive and therapeutic Pilates is effective for managing a range of chronic conditions .

Relevant education and experience to ensure accurate and tailored supervision is vital for safe effective provision of service.

Declaration of financial interest: none

Declaration of perceived interest: the author is a therapeutic Pilates teacher.

References

1. Centre for Health Services Research, Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Private Health Insurance for Natural Therapies in Part A. Overview report for Pilates 2014: University of Tasmania School of Medicine, .

2. Pedersen, B.K. and B. Saltin, Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 2015. 25: p. 1-72.

3. Posadzki, P., et al., Exercise/physical activity and health outcomes: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC public health, 2020. 20(1): p. 1-12.

4. AustralianGovernment. Eligibility of services for private health insurance general treatment benefits where they include elements of excluded natural therapies 2019 [cited 2023; Available from: https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20201115002252/https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-phicircular2018-69.

5. Hussein, H.M., et al., A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the pain-relieving effect of interferential current on musculoskeletal pain. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 2022. 101(7): p. 624-633.

6. Parreira, P.d.C.S., et al., Current evidence does not support the use of Kinesio Taping in clinical practice: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy, 2014. 60(1): p. 31-39.

7. Macedo, L.G., et al., Motor control exercise for persistent, nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Physical therapy, 2009. 89(1): p. 9-25.

8. Ganesh, G.S., P. Kaur, and S. Meena, Systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of motor control exercises in patients with non-specific low back pain do not consider its principles – A review. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 2021. 26: p. 374-393.

9. Pereira, M.J., et al., Efficacy of Pilates in Functional Body Composition: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2022. 12(15): p. 23.

10. Meikis, L., P. Wicker, and L. Donath, Effects of Pilates Training on Physiological and Psychological Health Parameters in Healthy Older Adults and in Older Adults With Clinical Conditions Over 55 Years: A Meta-Analytical Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 2021. 12: p. 17.

11. Hayden, J.A., et al., Some types of exercise are more effective than others in people with chronic low back pain: a network meta-analysis. Journal of physiotherapy, 2021. 67(4): p. 252-262.

12. Patti, A., et al., Physical exercise and prevention of falls. Effects of a Pilates training method compared with a general physical activity program: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore), 2021. 100(13): p. e25289-e25289.

13. Pilates, J.H. and W.J. Miller, Return to Life Through Contrology. The Millenium Edition ed. 1945, Incline Village, NV, USA: Presentation Dynamics Inc.

14. Zafeiroudi, A. and C. Kouthouris, Somatic Education and Mind-Body Disciplines: Exploring the Effects of the Pilates Method on Life Satisfaction, Mindfulness and Self-Compassion. 2022.

15. Fleming, K.M. and M.P. Herring, The effects of pilates on mental health outcomes: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Complementary therapies in medicine, 2018. 37: p. 80-95.

16. Pereira, M.J., et al., Benefits of pilates in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 2022. 12(3): p. 236-268.

17. Weber, M., et al., Effects of mind–body interventions involving meditative movements on quality of life, depressive symptoms, fear of falling and sleep quality in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2020. 17(18): p. 1-22.

18. Pinto-Carral, A., et al., Pilates for women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 2018. 41: p. 130-140.

19. Sánchez-Polán, M., et al., Prenatal Anxiety and Exercise. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 2021. 10(23): p. 5501.

20. Alpalhão, V., N. Cordeiro, and P. Pezarat-Correia, Kinesiophobia and Fear Avoidance in Older Adults: A Scoping Review on the State of Research Activity. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 2022. 1(aop): p. 1-10.

21. Oksuz, S. and E. Unal, The effect of the clinical pilates exercises on kinesiophobia and other symptoms related to osteoporosis: Randomised controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 2017. 26: p. 68-72.

22. de Freitas, C.D., et al., Effects of the pilates method on kinesiophobia associated with chronic non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2020. 24(3): p. 300-306.

23. Rahimimoghadam, Z., et al., Pilates exercises and quality of life of patients with chronic kidney disease. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 2019. 34: p. 35-40.

24. de Oliveira, B.F.A., et al., Pilates method in the treatment of patients with Chikungunya fever: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 2019. 33(10): p. 1614-1624.

25. Denham-Jones, L., et al., A systematic review of the effectiveness of Pilates on pain, disability, physical function, and quality of life in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Musculoskeletal Care, 2022. 20(1): p. 10-30.

26. Cemin, N.F., E.F.D. Schmit, and C.T. Candotti, Effects of the Pilates method on neck pain: a systematic review. Fisioterapia em Movimento, 2017. 30: p. 363-371.

27. Martini, J.D., G.E. Ferreira, and F. Xavier de Araujo, Pilates for neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 2022. 31: p. 37-44.

28. Rasmussen-Barr, E., et al., Summarizing the effects of different exercise types in chronic neck pain–a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2023. 24(1): p. 806.

29. Hayden, J.A., et al., Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(9).

30. Wells, C., et al., The Effectiveness of Pilates Exercise in People with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2014. 9(7).

31. Yamato, T.P., et al., Pilates for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(7).

32. Yamato, T.P., et al., Pilates for Low Back Pain: Complete Republication of a Cochrane Review. Spine, 2016. 41(12): p. 1013-1021.

33. Owen, P.J., et al., Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2019.

34. Fernández-Rodríguez, R., et al., Best exercise options for reducing pain and disability in adults with chronic low back pain: Pilates, strength, core-based and mind-body. A network meta-analysis. The journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 2022. 52(8): p. 1-49.

35. Parveen, A., S. Kalra, and S. Jain, Effects of Pilates on health and well-being of women: a systematic review. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy, 2023. 28(1): p. 17-12.

36. Grooten, W.J.A., et al., Summarizing the effects of different exercise types in chronic low back pain - a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2022. 23(1): p. 801.

37. Verville, L., et al., Systematic review to inform a World Health Organization (WHO) clinical practice guideline: benefits and harms of structured exercise programs for chronic primary low back pain in adults. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2023: p. 1-15.

38. Cancelliere, C., et al., Systematic Review Procedures for the World Health Organization (WHO) Evidence Syntheses on Benefits and Harms of Structured and Standardized Education/Advice, Structured Exercise Programs, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), and Needling Therapies for the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain in Adults. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2023. 33(4): p. 618-624.

39. Cancelliere, C., et al., Improving rehabilitation research to optimize care and outcomes for people with chronic primary low back pain: methodological and reporting recommendations from a WHO systematic review series. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2023: p. 1-14.

40. Kaeley, G.S., C. Bakewell, and A. Deodhar, The importance of ultrasound in identifying and differentiating patients with early inflammatory arthritis: a narrative review. Arthritis Res Ther, 2020. 22(1): p. 1.

41. Busija, L., R. Buchbinder, and R.H. Osborne, Quantifying the impact of transient joint symptoms, chronic joint symptoms, and arthritis: a population‐based approach. Arthritis Care & Research, 2009. 61(10): p. 1312-1321.

42. Azab, A.R., et al., Impact of Clinical Pilates Exercise on Pain, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Functional Ability, and Quality of Life in Children with Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health [Electronic Resource], 2022. 19(13): p. 25.

43. Raposo, F., M. Ramos, and A.L. Cruz, Effects of exercise on knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Musculoskeletal Care, 2021. 19(4): p. 399-435.

44. Kocyigit, B.F., et al., Assessment of complementary and alternative medicine methods in the management of ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatology International, 2022: p. 1-9.

45. Dantas, L.O., T.d.F. Salvini, and T.E. McAlindon, Knee osteoarthritis: key treatments and implications for physical therapy. Revista brasileira de fisioterapia (São Carlos (São Paulo, Brazil)), 2021. 25(2): p. 135-146.

46. Hazes, J.M. and J.J. Luime, The epidemiology of early inflammatory arthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 2011. 7(7): p. 381-390.

47. Ahlstrand, I., et al., Pain and daily activities in rheumatoid arthritis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2012. 34(15): p. 1245-1253.

48. Fenton, S.A., et al., Sedentary behaviour in rheumatoid arthritis: definition, measurement and implications for health. Rheumatology, 2018. 57(2): p. 213-226.

49. Song, P., et al., Global, regional, and national prevalence of asthma in 2019: a systematic analysis and modelling study. Journal of global health, 2022. 12.

50. Pilates, J.H., Your Health. The Millenium Edition ed. 1934, Incline Village, NV, USA: Presentation Dynamics Inc.

51. Latey, P., Updating the principles of the Pilates method - Part 2. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2002. 6(2): p. 94-101.

52. Kheirandish, R., R. Ranjbar, and A. Habibi, The effect of selected Pilates exercises on some respiratory parameters of obese sedentary women. KAUMS Journal (FEYZ), 2018. 22(2): p. 153-161.

53. Souza, C., et al., Cardiorespiratory adaptation to Pilates training. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 2021. 92(3): p. 453-459.

54. Yang, Z.Y., et al., Yoga for asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(4).

55. Santino, T.A., et al., Breathing exercises for adults with asthma. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2020. 2020(3): p. CD001277-CD001277.

56. Panagiotou, M., N.G. Koulouris, and N. Rovina, Physical activity: a missing link in asthma care. Journal of clinical medicine, 2020. 9(3): p. 706.

57. Pessôa, R.A.G., et al., Effects of Pilates exercises on cardiorespiratory fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 2023. 52: p. 101772-101772.

58. Sun, H., et al., IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes research and clinical practice, 2022. 183: p. 109119.

59. Esefeld, K., et al., Diabetes, sports and exercise. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 2021. 129(S 01): p. S52-S59.

60. Shawahna, R., et al., Exercise as a complementary medicine intervention in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with narrative and qualitative synthesis of evidence. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 2021. 15(1): p. 273-286.

61. Chen, Z., et al., Effect of pilates on glucose and lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Physiology, 2021. 12: p. 641968.

62. Melo, K.C.B., et al., Pilates Method Training: Functional and Blood Glucose Responses of Older Women With Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 2020. 34(4): p. 1001-1007.

63. Kaur, J., S.K. Singh, and J.S. Vij, Optimization of efficacy of core strengthening exercise protocols on patients suffering from diabetes mellitus. Romanian Journal of Diabetes Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases, 2018. 25(1): p. 23-36.

64. Orlando, G., et al., Neuromuscular dysfunction and exercise training in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A narrative review. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 2022. 183: p. 109183.

65. Jenkins, D.W. and A. Jenks, Exercise and Diabetes: A Narrative Review. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, 2017. 56(5): p. 968-974.

66. Han, T., et al., Associations of BMI, waist circumference, body fat, and skeletal muscle with type 2 diabetes in adults. Acta diabetologica, 2019. 56(8): p. 947-954.

67. Wang, Y., et al., Pilates for Overweight or Obesity: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 2021. 12: p. 13.

68. Batrakoulis, A., Psychophysiological adaptations to Pilates training in overweight and obese individuals: a topical review. Diseases, 2022. 10(4): p. 71.

69. Hicks, C.W. and E. Selvin, Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy and lower extremity disease in diabetes. Current diabetes reports, 2019. 19: p. 1-8.

70. Lazzarini, P.A., et al., Diabetes-related lower-extremity complications are a leading cause of the global burden of disability. Diabetic Medicine, 2018. 35(9): p. 1297-1299.

71. Orlando, G., et al., Sedentary behaviour is an independent predictor of diabetic foot ulcer development: An 8-year prospective study. diabetes research and clinical practice, 2021. 177: p. 108877.

72. Fuller, A.A., et al., Exercise in type 2 diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Current Geriatrics Reports, 2016. 5: p. 150-159.

73. Cozen, D.M., Use of Pilates in Foot and Ankle Rehabilitation. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 2000. 8(4): p. 395-403.

74. Cronin, E., et al., What are the effects of pilates in the post stroke population? A systematic literature review & meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2022.

75. Fleming, K.M., et al., Participant experiences of eight weeks of supervised or home-based Pilates among people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative analysis. Disability and rehabilitation, 2021: p. 1-8.

76. Kwok, J.Y.Y., K.C. Choi, and H.Y.L. Chan, Effects of mind–body exercises on the physiological and psychosocial well-being of individuals with Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary therapies in medicine, 2016. 29: p. 121-131.

77. Walter, A.A., et al., Complementary and integrative health interventions in post-stroke rehabilitation: a systematic PRISMA review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2022. 44(11): p. 2223-2232.

78. Sánchez-Lastra, M.A., et al., Pilates for people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders, 2019. 28: p. 199-212.

79. Arik, M.I., H. Kiloatar, and I. Saracoglu, Do Pilates exercises improve balance in patients with multiple sclerosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 2022. 57: p. 9.

80. Rodriguez-Fuentes, G., et al., Therapeutic Effects of the Pilates Method in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2022. 11(3): p. 14.

81. Mustafaoglu, R., I. Ahmed, and M.Y. Pang, Which type of mind–body exercise is most effective in improving functional performance and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease? A systematic review with network meta-analysis. Acta Neurologica Belgica, 2022: p. 1-14.

82. Ernst, M., et al., Physical exercise for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023(1).

83. Sherrington, C., et al., Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2019(1).

84. Sohail, B., et al., Recent advances in the role of rehabilitative therapies for Parkinson’s disease: A literature review. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 2023. 10(1): p. 85-105.

85. Qian, Y., et al., Comparative efficacy of 24 exercise types on postural instability in adults with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC geriatrics, 2023. 23(1): p. 522.

86. Kanis, J.A., et al., Assessment of fracture risk. European journal of radiology, 2009. 71(3): p. 392-397.

87. McLaughlin, E.C., et al., The effects of Pilates on health-related outcomes in individuals with increased risk of fracture: a systematic review. Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism, 2022. 47(4): p. 369-378.

88. da Silva Rocha, V., et al., Effect of the pilates method on people with osteoporosis: a systematic review. Manual Therapy, Posturology & Rehabilitation Journal, 2022. 20.

89. Fernandez-Rodriguez, R., et al., Effectiveness of Pilates and Yoga to improve bone density in adult women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One, 2021. 16(5): p. 14.

90. Anderson, B.D. and A. Spector, Introduction to Pilates-based rehabilitation. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Clinics of North America, 2000. 9(3): p. 395-410.

91. Mannino, D.M., COPD: epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest, 2002. 121(5): p. 121S-126S.

92. Portillo, E., et al., Evaluation of an implementation package to deliver the COPD CARE service. BMJ Open Quality, 2023. 12(1): p. e002074.

93. Russell, S., et al., Qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: views of patients and healthcare professionals. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine, 2018. 28(1): p. 2.

94. Priego-Jiménez, S., et al., Efficacy of Different Types of Physical Activity Interventions on Exercise Capacity in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): A Network Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2022. 19(21): p. 14539.

95. Yang, Y., et al., The effects of pursed lip breathing combined with diaphragmatic breathing on pulmonary function and exercise capacity in patients with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy theory and practice, 2022. 38(7): p. 847-857.

96. Latey, P., The Pilates method: History and philosophy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2001. 5(4): p. 275-282.

97. Morilla, J., C. Boquete-Pumar, and M. Garcia-Sillero, The Pilates Method as an alternative approach to recovery in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Retos-Nuevas Tendencias En Educacion Fisica Deporte Y Recreacion, 2022(45): p. 1009-1018.

98. Miranda, S. and A. Marques, Pilates in noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review of its effects. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 2018. 39: p. 114-130.

99. Park, J.J., et al., Efficacy of pelvic floor exercise for post-prostatectomy incontinence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology, 2022.

100. Pedriali, F.R., et al., Is pilates as effective as conventional pelvic floor muscle exercises in the conservative treatment of post‐prostatectomy urinary incontinence? A randomised controlled trial. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 2016. 35(5): p. 615-621.

101. Gomes, C.S., et al., The effects of Pilates method on pelvic floor muscle strength in patients with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: A randomized clinical trial. Neurourology & Urodynamics, 2018. 37(1): p. 346-353.

102. Fwu, C.-W., et al., Association of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes with urinary incontinence and chronic kidney disease: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2020. Journal of Urology, 2023: p. 10.1097.

103. Chu, S.W.F., et al., The role of mind-body interventions in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients – A systematic review of literature. Complementary therapies in medicine, 2021. 57: p. 102652-102652.

104. Ferreira, T.L., et al., Exercise interventions improve depression and anxiety in chronic kidney disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Urology and Nephrology, 2021. 53: p. 925-933.

105. Rijken, M., et al., Chronic Disease Management Programmes: an adequate response to patients’ needs? Health Expectations, 2014. 17(5): p. 608-621.

106. Norris, S.L., et al., Chronic disease management: a definition and systematic approach to component interventions. Disease Management & Health Outcomes, 2003. 11: p. 477-488.

107. Buchbinder, R.a.H., Ian., Hippocrasy. 2021, University of New South Wales: NewSouth Publishing.

108. Latey, P.J., Modern Pilates. 2001, Sydney, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

109. Latey, P., Curriculum - Graduate Certificate in the Pilates Method, in University of Technology, Sydney, UTS, Editor. 2000: Sydney.

110. Sanchez-Lastra, M.A., et al., Pilates for people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 2019. 28: p. 199-212.

111. Kruisbrink, M., et al., Disentangling interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention components. Disability and rehabilitation, 2022. ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print): p. 1-11.

112. Barros, B.S., et al., The management of lower back pain using pilates method: assessment of content exercise reporting in RCTs. Disability & Rehabilitation, 2022. 44(11): p. 2428-2436.

113. De Groef, A., et al., Best-evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 2: pain during and after cancer treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2019. 8(7): p. 979.

114. Chan, N.C. and K.M. Chow, A critical review: Effects of exercise and psychosocial interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors. Nursing Open, 2023. 10(4): p. 1954-1965.

115. Bo, K., S. Bratland-Sanda, and J. Sundgot-Borgen, Urinary incontinence among group fitness instructors including yoga and pilates teachers. 2011. 1(3): p. 370-3.

116. Menezes, E.C., et al., Effect of exercise on female pelvic floor morphology and muscle function: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal, 2022: p. 1-15.

117. Lausen, A., et al., Modified Pilates as an adjunct to standard physiotherapy care for urinary incontinence: a mixed methods pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BMC women's health, 2018. 18(1): p. 16.

118. Puljak, L. and C. Arienti, Can physical activity and exercise alleviate chronic pain in adults?: A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 2019. 98(6): p. 526-527.

119. Rivera-Torres, S., T.D. Fahey, and M.A. Rivera, Adherence to exercise programs in older adults: informative report. Gerontology and geriatric medicine, 2019. 5: p. 2333721418823604.

120. Mitchell, M.S., et al., Financial incentives for exercise adherence in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of preventive medicine, 2013. 45(5): p. 658-667.

121. Collado-Mateo, D., et al., Key factors associated with adherence to physical exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: an umbrella review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2021. 18(4): p. 2023.

122. PAA. Pilates Assocation Australia. Scope of practice 2023 [cited 2023; Available from: https://tinyurl.com/2uf6hf9v.

123. Reid, H., et al., Benefits outweigh the risks: a consensus statement on the risks of physical activity for people living with long-term conditions. British journal of sports medicine, 2022. 56(8): p. 427-438.

124. Byrnes, K.M., P.-J.M. Wu, and S.P. Whillier, Is Pilates an effective rehabilitation tool? A systematic review. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 2017. 22(1): p. 192-202.

125. Yang, Y.M., et al., Spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture complicated with perforation of the stomach during Pilates. Am J Emerg Med, 2010. 28(2): p. 259.e1-3.

126. Ergün, M., İ. Yörük, and O. Köyağasioğlu, Simultaneous bilateral shoulder dislocation during pilates reformer exercise: A case report. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2022: p. 1-8.

127. Lorenc, A., et al., Scoping review of systematic reviews of complementary medicine for musculoskeletal and mental health conditions. BMJ open, 2018. 8(10): p. e020222.

128. Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions. 2017 [cited 2023.

129. ProductivityCommission, Innovations in Care for Chronic Health Conditions, in Innovations in Care for Chronic Health Conditions-Productivity Reform Case Study, P. Commission, Editor. 2021: Canberra.

130. Booth, F.W., et al., Role of inactivity in chronic diseases: evolutionary insight and pathophysiological mechanisms. Physiological reviews, 2017. 97(4): p. 1351-1402.

131. Bhattacharyya, K.K., et al., Mind-body practices in U.S. adults: Prevalence and correlates. Complementary therapies in medicine, 2020. 52: p. 102501-102501.

132. Bodenheimer, T., et al., Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama, 2002. 288(19): p. 2469-2475.

133. Reynolds, R., et al., A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract, 2018. 19(1): p. 11.

134. Booth, F.W., C.K. Roberts, and M.J. Laye, Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive physiology, 2012. 2(2): p. 1143.

135. Nancarrow, S.A., Six principles to enhance health workforce flexibility. Human resources for health, 2015. 13(1): p. 1-12.

136. Naylor, J., C. Killingback, and A. Green, What are the views of musculoskeletal physiotherapists and patients on person-centred practice? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2023. 45(6): p. 950-961.

137. van Schalkwyk, M.C., et al., The best person (or machine) for the job: Rethinking task shifting in healthcare. Health policy, 2020. 124(12): p. 1379-1386.

138. Giannakou, I. and L. Gaskell, A qualitative systematic review of the views, experiences and perceptions of Pilates-trained physiotherapists and their patients. Musculoskeletal Care, 2021. 19(1): p. 67-83.