1. Introduction

Anecdotal vs scientific evidence

Do you want to write articles, conduct a study or present a case? Either way you need evidence to support the purpose.

Research by level of evidence

What does “peer-reviewed” mean and why is it important?

First steps to becoming research-savvy:

Do you want to write articles, conduct a study or present a case? Either way you need evidence to support the purpose.

- Anecdotal evidence is evidence collected in a casual or informal manner and relying heavily or entirely on personal testimony.

- Compared to other types of evidence, anecdotal evidence is generally regarded as limited in value due to a number of weaknesses.

- Scientific evidence results when a theory or hypothesis is tested objectively following scientific standards in a controlled environment.

- When people talk about “evidence-based” practice, they usually mean scientific evidence.

- The before-and-after photo of a client after an exercise intervention is evidence, but it has limited value due to the many ways they could be manipulated.

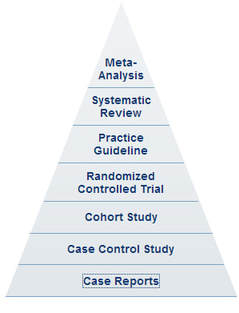

Research by level of evidence

- Case reports are the first articles published on new topics so they make up the base of the pyramid. As we progress up the pyramid, the studies become more evidence-based and less numerous.

- Meta-Analyses are at the top of the pyramid because they review and statistically analyze other articles and can only be written after much other research has been done on a topic. There are fewer of them but they offer very strong evidence.

What does “peer-reviewed” mean and why is it important?

- Definition: Evaluation of scientific, academic, or professional work by others working in the same field.

- The reviewers are carefully evaluating the quality of the submitted manuscript.

- They check the manuscript for accuracy and assess the validity of the research methodology and procedures.

- They suggest revisions.

- If they find the article lacking in scholarly validity and rigor, they reject it.

- This process guarantees a high scientific standard.

- Peer-reviewed journals are deemed superior.

- Please note not all articles indexed in scientific databases and journals are necessarily peer-reviewed. In fact, Pubmed (see "where to find research articles") does not only not indicate whether an article is peer-reviewed or not, it also doesn't allow to search for peer-reviewed articles only.

First steps to becoming research-savvy:

- Taking time to find and read articles of interest using trusted sources (below).

- Read critically. Often research studies are reduced to catchy sound bites, which may or may not accurately reflect their findings.

- Can you think of reasons why an intervention is rated as effective for the participants even if it is not? What was the coach’s skill level? How many sessions over what period of time? How many participants were questioned/tested?

- Start to think critically about what you hear colleagues say: Is a certain exercise really superior to another for a certain muscle group? Can you/should you aim to improve a client’s posture and why?

- Join an evidence-based fitness organization such as ACSM and NSCA in order to have access to latest studies.

- Like (and have them show on top of your news feed) the social media pages of organizations that publish and discuss research, such as: ACSM, NSCA, Physical Therapy: Practice, Education and Networking, BJSM, Advanced in Clinical Education / N.A., NYT – Health, Barbell Rehab, Unchained Physio, Clinical Athlete, Breakingmuscle, Brent Brookbush.